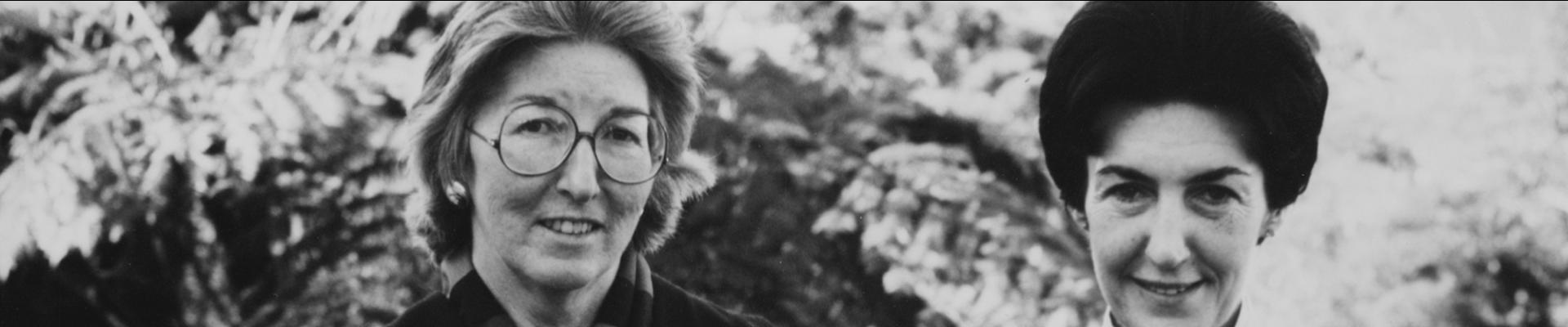

A book of letters should be quick and easy to compile. At least, that’s what I presumed Brigitta Olubas invited me to co-edit a collection of the letters exchanged by the great Australian novelists Shirley Hazzard and Elizabeth Harrower. All the writing has been done by the correspondents, I thought, and the editors simply have to organise the most compelling parts into a chronological narrative. But, as we discovered, these two had written to one another for 40 years, around 400,000 words in hundreds of letters, most of which survive among their respective papers in the State Library of NSW and the National Library of Australia. Brigitta and I worked intensely together for more than a year on Hazzard and Harrower: The letters, although the story had begun many years earlier in New York.

A professor of English at the University of NSW, Brigitta is an expert on both writers, and in 2022 published an authorised biography of Hazzard to international acclaim. As a literary journalist, I had interviewed both women and am researching Harrower’s life for a biography. So we brought different perspectives and research skills to this multi-layered friendship, which was largely carried on through letters.

Elizabeth Harrower was born in Newcastle in 1928 and Shirley Hazzard in Sydney in 1931. They were children of the Depression and War, self-taught intellectuals and writers. When they wrote their first letters to each other in the late 1960s, both were rising literary talents in Australia and abroad.

Hazzard had spent her early childhood in Sydney, before her father’s overseas postings as Australian Trade Commissioner took her, finally, to New York, where she worked as a stenographer for the United Nations. There she met and married Francis Steegmuller, an American biographer of Flaubert and Cocteau. For the rest of their lives the couple moved between homes in New York, Naples and Capri, writing and mixing in high cultural circles. Hard-working Hazzard had early success with short stories that were published regularly in The New Yorker magazine from 1961. She crafted subtle novels about love, heartbreak, war and displacement: The Evening of the Holiday (1966), The Bay of Noon (1970), her masterpiece The Transit of Venus (1980) and her final work, The Great Fire (2003), which won the National Book Award in the United States and the Miles Franklin Award in Australia. She also wrote non- fiction about the UN and literary travel memoirs.

The Steegmullers visited Australia just four times but were tied to Sydney by Hazzard’s divorced mother. Vivacious and demanding, Kit Hazzard became a friend of Elizabeth Harrower and grew increasingly dependent on her. They were introduced in 1966 by Norma Chapman, who owned a bookshop near Kit’s home in Potts Point.

Harrower had a tumultuous childhood, left by her separated parents to live with her Scottish- born grandmother in Newcastle. When her mother later married an accountant of dubious reputation, Harrower moved with them to Sydney. In 1951 the three travelled to Europe, where Harrower stayed alone for eight years in Scotland and then in London, free at last to study, travel and write. She quickly published three novels: Down in the City (1957), The Long Prospect (1958) and The Catherine Wheel (1960), before settling back into office jobs in Sydney that would both support, and slow, her writing. Her masterwork, The Watch Tower (1966), marked the epitome of her observant social and psychological studies of destructive relationships between men, women and children.

Around the time The Watch Tower and The Bay of Noon were published, Kit Hazzard connected the two writers. While visiting her daughter in New York in 1966, she wrote Harrower an effusive letter, to which Hazzard added a polite note. She thanked Harrower for compliments on her fiction, passed on by Kit, and wrote that she was keen to read Harrower’s books, and hoped they would meet. None of them had an inkly of how tightly plaited they would become.

Since the time I found your first story for myself I have taken an exclusive sort of interest in your work … Then recently I so enjoyed meeting your mother. We were well disposed towards each other, of course, because of our common enthusiasm … (Harrower, November 16, 1966)

In 1970, Harrower submitted her fifth novel, In Certain Circles, to her publisher just before the sudden death of her mother, Margaret. Shocked and grieving, and dissatisfied with her book, she withdrew the manuscript. In the next decade she published some short stories and talked endlessly of her desire to write another novel, urged on by friends including Hazzard and Patrick White, who blamed ‘too many vampires’ for sucking up her time. But Harrower devoted herself instead to Australian Labor Party politics, and to needy friends, such as Kit Hazzard. Her public career went quiet for decades, until her novels were reissued by Text Publishing from 2012, and In Certain Circles and a short story collection published for the first time. She thrived on the renewed attention until she died in 2020, four years after Hazzard.

Most of Harrower’s energy for writing, we found, went into letters to her many friends and especially to Hazzard, who was an equally prolific correspondent. Their written exchanges provide an important account of their personal and professional lives, the determination needed to be a writer, their extensive reading, their literary networks, and world affairs. Hazzard was aghast at the Watergate scandal that ended Nixon’s presidency, and Harrower wrote a firsthand report from Canberra about the Dismissal:

Telephone rings. I hear Christina [Stead] saying many times, ‘But that’s terrible. That’s terrible … Malcolm Fraser is Prime Minister. Kerr has got rid of Whitlam.’ Horror … Finally knocked off some Nescafe and took taxi to Parliament House … (Harrower, November 17, 1975)

While Brigitta Olubas was researching Shirley Hazzard: A writing life, she found Harrower’s forgotten letters among papers in the basement of Hazzard’s Manhattan apartment. She helped to organise Hazzard’s papers and books after her death in 2016, lodging them in the State Library of NSW and Columbia University Library in New York. Harrower had placed the letters she received from Hazzard with her papers in the National Library of Australia in Canberra, placing an embargo on them until both women had died. Brigitta’s plan for an edited volume had to wait.

I had interviewed Hazzard in New York in 1993 and Italy in 2006 when we travelled to Rome, Naples and Capri, and interviewed Harrower several times in Sydney. I remained friendly with both women in their last years. I had read Harrower’s letters at Hazzard’s apartment in 2017, and was delving into the mysteries of Harrower’s life when Brigitta suggested we collaborate on a book. Two authors, two editors — it made sense. From the start, Brigitta took Hazzard’s part and I took Harrower’s. We did not have the challenge David Marr faced, for instance, after he wrote Patrick White’s biography and then had to seek out White’s letters from dozens of recipients around the world before he could turn them into a book. We not only knew where our material was, we knew what it meant.

Our first massive task was to photograph the original letters in the reading rooms of the respective libraries and then to transcribe them. Fortunately, not only did Hazzard and Harrower write elegant and grammatically perfect sentences, they typed most letters so they were clear to read. What a miracle it was to hold those sheets of paper, blue aerograms and postcards imprinted with ink that seemed fresh from their hands. When we interleaved the letters into a single, massive document we had the pleasure of seeing two strong voices in dialogue. Comments from one suddenly made sense as the other replied, and their relationship sprang back to life.

What began as an occasional exchange quickly plunged into intimacy, driven by Kit’s erratic behaviour (they used shorthand MM and YM — My Mother, Your Mother – for the oft-mentioned Kit). Hazzard worried and did what she could from afar, but she and her sister, Valerie, had largely distanced themselves from their intractable mother. Kit was diagnosed with manic depression (now known as bipolar disorder) and was always restless, wanting to travel and move to new homes. She could be loving and abusive to those who helped her, and was at times suicidal.

We do not know whether MM is at Sydney, Hawaii, Los Angeles, New York, London, or Devon. And, after all that has passed, can hardly summon up a flicker of curiosity. (Hazzard, June 22, 1977)

Harrower engaged doctors, resolved all kinds of emergencies, and provided company for her lonely friend. Hazzard and Steegmuller, who were grateful in return, sent money and pressed Harrower to visit them in Italy and New York. The penpals first met in London in 1972, and then several times in Sydney, where Harrower introduced Hazzard to her network of contacts, including former prime minister Gough Whitlam. But when Harrower — a reluctant traveller — eventually visited Rome, Naples and Capri in 1984, proximity tested their affection. Tensions between them, only hinted at in their letters, were made explicit in journals and conversations with others.

When they had continents between them, however, their friendship ran warm and deep. Common interests and concerns flow through the letters: their need to write, and the obstacles to writing; their broad taste in literature and the arts; their love of natural beauty, their left-wing political views and their joint despair that learning, decency and the planet itself were all in decline. They shared confidences about publishers, writers, friends and traitors, and they consoled and celebrated each other. Harrower immediately read The Transit of Venus, twice, and declared to its author that the novel was ‘a stunning, dense, complex work’, though she told others she only liked Hazzard’s early novels.

I am writing this instant word to say how greatly prized and loved your generous words are – they make me happy in a way no one else’s could, and I am delighted my book gave you, of all readers, pleasure … (Hazzard, March 10, 1980)

Sometimes Brigitta and I had to decipher what we were reading about, and crosscheck comments and fill gaps, so we could explain the background in our introduction to the book. There are breaks in the correspondence when letters were lost, or conversations were held by telephone or in person. Harrower, in particular, writes discreetly about unnamed ‘friends’ or ‘my Mob’. As a single, sociable woman she was often at the mercy of domineering personalities, like one of the characters in her own novels.

In 1973, for example, Harrower wrote to Hazzard that she had agreed reluctantly to join friends on a cruise to Japan. But, she added, Cynthia Nolan, wife of the artist Sidney, was furious about this decision and refused to speak to her. Harrower pressed on, but left the ship at Brisbane and went into hiding. Reading her letters about the experience to Hazzard, we wondered who could have caused such turmoil.

So, back at the National Library I hunted through boxes of Harrower’s letters to other friends. Sure enough, she had written to Christina Stead that she was going on a cruise (for six weeks!) with the writer Kylie Tennant, and Tennant's daughter and father. Tennant was one of Harrower’s closest friends, but her family’s chaos and tragedies caused Harrower great anxiety. This, then, was the key to her abandoning ship. Cynthia Nolan knew the history of their relationship and was right to warn Harrower, but she was suffering her own mental breakdown. Her overreaction only added to Harrower’s distress.

Our challenge lay in how to represent all this complexity while reducing the overall length of the correspondence by three-quarters. Brigitta and I met many times to read and argue — and mostly agree — about what to drop. Pages and pages of Kit’s travails had to go, as did some repetitive political discourse, daily minutiae and minor illnesses. We narrowed the cast of characters to the most significant people in Hazzard’s and Harrower’s lives; a few went for reasons of privacy. We kept anecdotes (often involving Kit) that made us laugh every time, or weep as the letters faded to an end. Each round of cuts became more painful. But we are satisfied that the result is a rich and enduring biographical narrative, an ode to women’s friendship a an elegy to the great art of letter writing.

Susan Wyndham is a 2024 National Library of Australia Fellow, working on a biography of Elizabeth Harrower. She has been literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and New York correspondent for The Australian. Hazzard and Harrower: The letters is published by NewSouth.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2024.