Hidden amongst the stems of wheat, I watch as thousands of mice burn. Most of them are already dead, poisoned by bait the farmer positioned strategically around the paddocks. But not all. The man stands by his tractor, clad in dusty overalls and Blundstone boots, observing the conflagration. He has been careful to keep the fire contained in an old oil drum. If it spread to his crops, the flames would not stop until they had consumed half the shire — more than the mice might, even. Admittedly their wave of destruction is not petty. But it is born of necessity. The weather has changed. Conditions are ripe for procreation. There are many more of them this year than ever before. Millions. And they are hungry. Are they to be blamed for feeding their pups? In following their instinct, do they deserve to be murdered? I close my eyes and try to block out the final squeals of agony echoing around the drum.

The farmer cannot hear the cries of the dying. He removes his hat and runs a rough palm through thinning hair. The sun claws at his bald spot. Like most of his kin, the man believes that his desires outrank everyone else’s suffering. He thinks that devotion to progress is a virtue, conveniently choosing to forget that selfishness is sinful. Not to mention counterproductive. Would it not better serve the man to work alongside us? To share his bounty, rather than hoard for his own ennoblement? Humans harvest enough food to feed all their brethren and yet children starve. Families struggle to make ends meet, to put food on the table, if they even have a table. Meanwhile crops are destroyed, wine is poured into the sea, products are removed from the shelves of the great corporate benefactors touting low, low prices and cast into the refuse rather than given to the hungry. Theirs is a cruel and turbulent world.

And yet part of me sees good in them. In this benevolence, I am an outlier in the murine community. I am the one who notices the farmer’s trembling hand, the sharp intake of breath as he surveys what is left of this little corner of the world that he has fought so hard to preserve. He senses an ending. Change is coming, for all of us. We are powerless in the face of flood and fire. The land always wins.

What are we to do? How should we live? What do we really need? Perspective is a great leveller, and I for one advocate for harmonic order and tidiness whilst we walk the earth, be it on two legs or four. We must learn to discard the unnecessary ties that bind us to the past. Our path in this world should be clear and steadfast. Life is easier once you accept that everything will work out as it should even if you lack the accoutrements of prosperity. I, Gideon the Antechinus, a humble Australian marsupial shrew, feel pity for the farmer despite his pernicious crimes on mousedom. And so, I shall act, extend an olive branch to the man. I will tidy his shed. As lodestar of neatness and my personal idol Marie Kondo once said, if you are going to put your house in order, do it now.

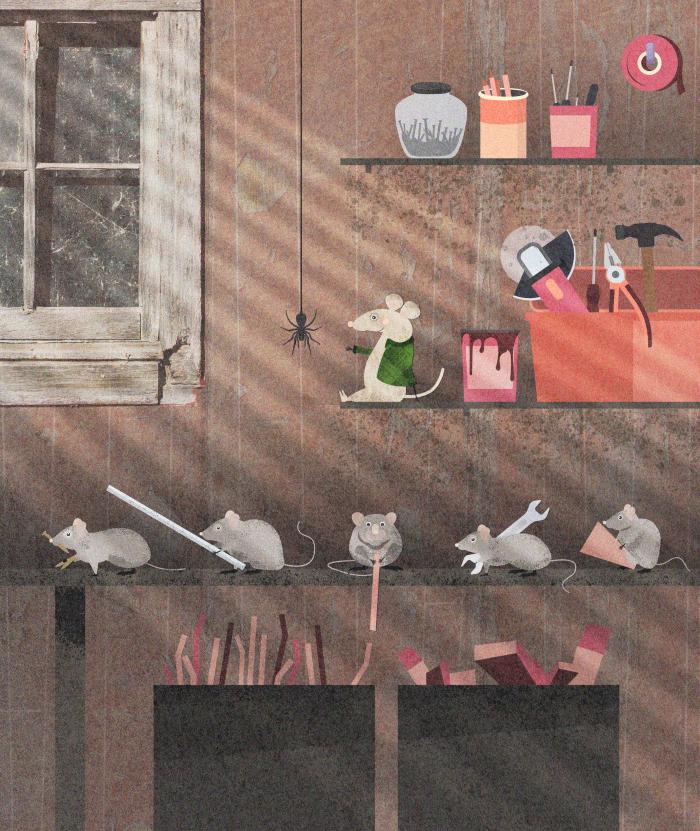

I share my home in the shed with a cauldron of tiny bats and a cluster of arachnids. Neither species seems especially interested in keeping the place spick and span. In fact, the spiders are bent on smothering every corner with their webs. I foolishly assumed they would be motivated by an innate sense of order. Web spinning requires structure and method, after all. But no, they don’t care. I tried talking to one of the big huntsmen about maintaining tidiness and he told me to rack off and mind my own business. No wonder humans hate them. So rude.

‘Tidying is merely the act of confronting oneself,’ I told him, paraphrasing my role model Marie. The door is not usually locked but moments later I hear him securing a padlock across the bolt.

It is surprising that he has not learnt one of Marie’s essential lessons by now. When you treat what is precious to you well, that object, or entity, always responds in kind. Human males are so tiresomely predictable. They are gullible and easily influenced by authority figures and yet possess a remarkable lack of self-awareness. The farmer is married, and yet he lives alone on this ramshackle two-hundred-acre property that tumbles further into decline with each passing year. He was never abusive towards his wife and children. He simply neglected them, treated them like pieces of machinery that were essential in the running of a farm. They served his needs, whilst he steadfastly denied the existence of theirs.

I suppose negation is a form of abuse, in a way, one that is difficult to quantify and rarely discussed. His kids came of age and left for more cosmopolitan climes, rarely returning to visit, and only then out of dutiful obligation and without enthusiasm. His wife, after managing to wrangle control of their bank accounts with the assistance of a solicitor, rents a two-bedroom unit on the coast. She attends Pilates classes and tries not to call him when she feels guilty for leaving.

The man is not oblivious to emotion. In fact, his turmoil has grown keener when faced with naught but his own thoughts. His grain silo overflows with regret and terror and loneliness. He acknowledges everything is his fault, wishes he could wind back the clock and behave in a more tender and conscientious manner. And so, he finds himself, like so many of his kind, trapped in an impasse. He cannot see a way forward, nor can he ever go back.

He has returned to the shed, clutching a bright yellow plastic bag with black lettering that reads: JB Hi-Fi, Biggest Range, Cheap Prices.

From the bag the farmer produces a box containing a tiny video camera, which he sets up on a cute tripod. It is not a GoPro. It is a cheap knock-off brand. He positions the camera on a shelf overlooking the workbench and nods, pleased with himself. He mumbles something about ghosts.

Bless. He thinks the shed is haunted by obsessive compulsive phantoms.

‘Tidying is a celebration!’ I cry out, as a motivational slogan to encourage my fellow tiny creatures. They are working hard to arrange the farmer’s tools into some semblance of order. Several half-empty crates have been dragged to the base of the bench using a complex system of string and pulleys. Three teams of mice separate socket wrenches, screwdrivers and allen keys on the table above, pushing the gleaming metal tools over the edge so they fall into the appropriate container below. The crew took to the task with relish, eventually, once I had convinced their representative that such efforts would pay dividends.

‘Mackenzie Splayfoot the Fourteenth,’ their leader said, shaking my paw after we met by the hole on the western side of the shed the previous morning. ‘Hear you’ve got a job of work for the horde.’

‘If you’ll follow me, Miss Splayfoot, I’ll show you around the site,’ I said.

Upon explanation of the challenges, Mackenzie was dubious.

‘Lot of health and safety issues here,’ she said, peering around the gloomy interior of the shed. ‘Sharp objects, precipitous falls, unidentified fluids. All risks to our members. I fail to see why the CFMEEU should offer their assistance.’

Mackenzie is a representative for the Country Field Mouse Environmental Engineering Union.

‘Try to visualise the lifestyle your members might enjoy if they were living in a clutter-free space,’ I told her. ‘The process of tidying will help them identify their values, reducing doubt and confusion.’

Mackenzie thought about this, distractedly kicking at an ear with her hind leg.

‘I do like a fixer-upper,’ she said. ‘This place has potential.’

‘I am honour bound to point out that we will have an audience,’ I told her. ‘Several, in fact.’

I indicated the Zero-X camera and waved to Rafferty, who by now had assembled a cluster of arachnids to watch. Several appeared to be spinning camp chairs.

‘We’ll work under cover of darkness to better conceal our efforts,’ she said. ‘Let’s talk remuneration. Our members expect the award rate.’

‘And what is that, at the moment?’ I asked.

‘Six wheat seeds each per day,’ she said. ‘A caterpillar for weekend penalties.’

‘I am sure that can be arranged,’ I said, without having the slightest clue how I would provide such a bounty.

A settlement was thus reached and now I find myself standing sentinel at the hub of nocturnal activity, agog at the industry of my murine cousins. Mackenzie moves amongst the workers, berating any who exhibit laziness or inattention.

‘Mate, that’s a Phillips head screwdriver, not a flathead,’ she says to one hapless mouse. ‘Bin four, mate, bin four.’ She shakes her snout in dismay as the mouse drags the tool to the correct spot on the precipice and pushes it into the void. The screwdriver clatters into the bucket below.

‘Bloody apprentices,’ Mackenzie mutters.

The moon is almost full tonight. Its pale light filters through the slats in the shed, casting a dramatic glow over proceedings on the workbench. I glance up at the camera. A green light blinks. The performance is being recorded.

When I emerge from my nest inside the folds of a discarded cushion forgotten in a box at the rear of the shed, the farmer is waiting. He stands stock still by the workbench, eyes fixed on the marvellous new set-up we have built for him. I slip warily out of the nest and discreetly make my way to the mounting platform behind the bench. Some of the horde, also awakening from slumber, cautiously poke their snouts out from dark corners.

‘I feel like an idiot saying this,’ the farmer says, clearing his throat. ‘But, hello? I don’t suppose you understand me.’

I scurry up the steps of the platform we constructed and emerge from behind a tin of paint so the man can see me. It is a calculated risk. A lot depends on the next few moments. He peers down at me. I preen my whiskers in greeting.

‘Hello, little mate,’ he says. ‘I’ve been watching you on the camera. Are you the leader?’

Mackenzie Splayfoot rolls her eyes. She leans against a rusted can, in which I’ve placed every one of the farmer’s pencils.

‘Typical,’ she says. ‘The boss takes credit for the graft of the proletariat.’

Unfortunately, the farmer cannot understand our language, which is made up of a dizzying range of tonal squeaks. Much too complex for humans.

Excited by this potential breakthrough in interspecies communication, I dart back and forth between the receptacles, pointing out our work to the man. He nods appreciatively. I then reveal our crowning glory by pulling back a cloth to reveal a fully disassembled carburettor from his vintage motorcycle. I had observed him struggling with it on several occasions. Tiny paws made light work of the seized piece of machinery.

The farmer makes a soft honking sound and then begins to sob. I wait for him to compose himself.

‘Sorry,’ he says, wiping his eyes on a sleeve. ‘It’s just … it’s been so long since anyone showed me kindness.’

Dozens of mice have emerged from their nests now, and even Rafferty and his cluster of arachnid reprobates watch from above. The farmer takes a moment to pull himself together.

‘Righto,’ he says. ‘I’m sorry for laying bait in the fields. I had no idea.’ He crouches by the bench, so we are at eye level. It is somewhat disconcerting, but I am not afraid. ‘Tell you what, little fella,’ he says. ‘If you can forgive me, I’ll provide food for all of your kind, provided you leave the crops alone.’

I glance across at Mackenzie.

‘Make the deal,’ she says, without hesitation. In lieu of shaking paws, I nod assent.

The farmer’s eyes widen in astonishment. He stands upright and places his hands on his hips, surveying the workspace.

‘You’ve done a bang-up job here,’ he says. A light goes on upstairs. You can see it in his eyes. ‘Don’t suppose you’d be interested in having a go at my place? It’s like a bomb went off in there.’

Mackenzie Splayfoot does not require any further encouragement. She howls for the workers to assemble and within moments, the horde is running, darting and leaping past the bewildered human, out of the shed and up the hill towards the main farmhouse.

The farmer turns to me, shakes his head and laughs. I want so badly to tell him that no matter how wonderful things used to be, we cannot live in the past. The excitement of the now is more important. We must spark joy.

Author’s Note

In 2023, Welsh wildlife photographer Rodney Holbrook set up a camera in his shed after noticing that his bench was being tidied every night. The resultant footage is remarkable. Google ‘Welsh Tidy Mouse’ for a heart-warming treat.

Chris Flynn is the author of the bestselling novel Mammoth and the award-winning collection of short stories Here Be Leviathans. Both are published by UQP. He is appearing at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on Wednesday 22 May.

This story appeared in Openbook winter 2024.