One of the central figures of the First Fleet was chief surgeon John White. He was a well-connected and skilful medical practitioner who lived at the hospital on the western shores of Warrane (Sydney Cove) for more than six years, longer than many among the senior staff originally sent out to Botany Bay. The strain of his work was relentless, especially after the arrival of the appalling Second Fleet, when more than 500 seriously ill convicts overwhelmed his small prefab and timber hospital complex.

By 1792, White was pleading to be relieved. When he was finally allowed home on leave two years later, he never seriously contemplated returning. He left behind his de facto partner, the Second Fleet convict Rachel Turner, although he always recognised their son Andrew Douglas White, who was born in 1793 and went to school in England. He joined the British Army with his father’s support, later fighting at Waterloo.

In Sydney, White clearly took consolation in his many rambles in the bush, not least because he was determined to collect almost industrial quantities of the local flora and fauna for his patrons in England. An enormous part of this project involved him supervising the creation of hundreds of watercolours in his private studio. This was a major undertaking: the hard-worked convict artist Thomas Watling, pressed into his service after he arrived in late 1792, was disheartened by the workload, reviling White as ‘a very mercenary sordid person’.

White’s dedication to collecting did lead directly to one of the most important First Fleet accounts, his Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (1790). Illustrated with plates by Sarah Stone and others, the book is a landmark work of Australian natural history, especially its exquisite hand-coloured edition. By turns wry and haughty, it recounts his voyage out and the first ten months of the settlement, somewhat edited and cleaned up before publication in London. None of the original manuscripts have survived.

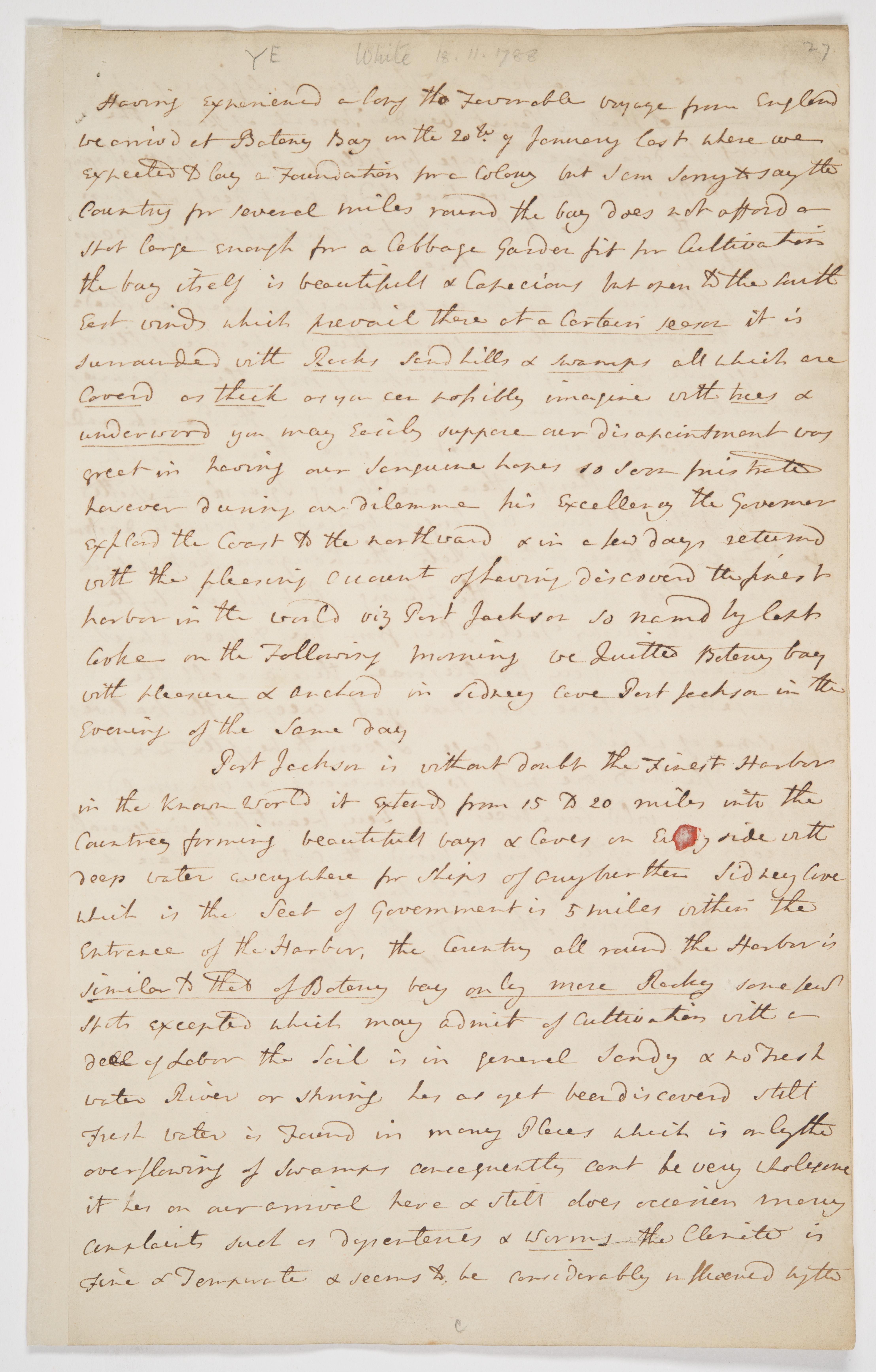

The loss of most of White’s papers makes it all the more remarkable that a transcript of one of his letters has been hidden in plain sight for more than a century in the Library’s Sir Joseph Banks Papers. This letter has hitherto been catalogue as an ‘extract’ from White’s published Journal, but it is very clearly a private letter to an unknown recipient dated Sydney, 18 November 1788, transcribed by Banks in his unruly hand.

The letter has a markedly bitter and downcast tone quite unlike anything in his Journal. It starts with a scathing comment on how the proposed site of the settlement at Botany Bay had proven to be completely uninhabitable — a barren landscape with not even a ‘spot large enough for a Cabbage Garden fit for Cultivation’. White adds his opinion that Port Jackson, while admittedly a beautiful harbour, had a difficult ground for ships. Supplies were scarce or inferior, the situation too remote, rations short.

More alarmingly for a medical man, the fresh water supply was doubtful. White described it as little more than overflow from the ‘swamps’ to the south of the settlement and therefore the source of ‘many complaints such as dysenteries & worms,’ which, by inference, White must have had to treat in his makeshift hospital. All of this, he continued in one of the most significant passages, was taking place against the backdrop of tenacious and violent resistance from the local tribes, who ‘have murthered several of the convicts & one Marine besides wounding many more’.

This was the unvarnished opinion of a senior figure in government and is a trenchant denunciation of the whole project. It was White’s opinion that every ‘gentleman’, barring two or three, sincerely wished that ‘the expedition may be recalled’.

The tone is so frank that it must have been written to someone on whom White thought he could rely for discretion. Whomever the recipient was, White would likely not have thanked them for forwarding it to Banks, who was not a tremendous enthusiast for blunt criticism from his social inferiors. Banks certainly kept a wary eye on him, and although he subscribed for a copy of White’s book (now held in the British Library), it is clear that he was keeping the surgeon at arm’s length.

The letter can now also be compared with another rediscovery, a letter White wrote the very next day, 19 November 1788, to the philosopher and prison reformer Jeremy Bentham. Recently transcribed for the Bentham Papers at University College London, this letter dramatically confirms White’s strident dislike for the colony, writing, ‘as this is only for your private reading, I will freely tell you that I have been from one extreme of North America to the other, through all the West India Islands on the Mosquito Shore and other parts of the Spanish Main, and in the course of my peregrinations I never saw so unpromising miserable a Country as this is.’

White’s privately expressed pessimism would have a significant echo in a much later letter he sent to another contact in London, which was so explosive it was printed in one of the opposition newspapers. Dated from Sydney, 17 April 1790, it proves that White’s opinion only hardened as the privations of life in the colony after the wreck of the Sirius really took hold. He was living, he said, in ‘a country and place so forbidden and so hateful, as only to merit execrations and curses’. Once again, Banks took a cutting for his archive.

Taken together, the letters show that in private, White was vitriolic about the settlement from the very beginning; little wonder that he had no hope of ever publishing his long-mooted second book.

Matthew Fishburn is a Sydney-based writer and rare book dealer.

This story appears in Openbook autumn 2024.