In a 2015 talk to students and colleagues at Sydney College of the Arts, Bronwyn Bancroft shared an early memory. ‘From the very first time that I could discern shade from light, line from tone, I have been in love with art and the creation of art.’ She went on, ‘Trees, bark, rocks and sky set me on a journey to record and exact the beauty of nature, through my eyes. I am here today because I am a creative creature. But it is a long way from where I began.’

Bancroft has been exhibiting her art nationally and internationally, to great acclaim, for over three decades. Since 1992 she has written or illustrated — sometimes both — 47 books. Like her books, her art is vibrant and driven by heartfelt stories and memories that powerfully represent Aboriginal culture, experiences and knowledge. Her fearless voice, sharing truths about Country, kinship, family and environmental degradation, has echoed far and wide. This mother, truth seeker and artist demands a reframing and decolonising not only of our written, oral and visual shared history, but of our society at large.

Ahead of the exhibition that has emerged from the inaugural NSW Aboriginal Creative Fellowship awarded to her in 2021 — a partnership between the Library and Create NSW — Openbook celebrates Bancroft’s work and art in her own words, and those of her son Jack and daughter Ella. The Bancroft family’s words also appear in the exhibition, weaving around pieces that entwine the central themes of Country, family and shared history. Curator Cherokee Lord also shares her experience of visiting the artist’s studio on Country and Damien Webb, Manager Indigenous Engagement, reflects on the exhibition.

Mum. Bronny B.

Jack Manning Bancroft

Cackling laughter. Firepit burning. People moving.

Mum.

A streak of colour traverses the footpaths of inner-city Sydney, arresting attention, seamlessly weaving, floating on another frequency. Alive to the magic. Amongst the dull and gray.

Mum. Bronny B.

Determined, focused, don’t you dare say she can’t do it. Strong. Relentless. Driven. Open. Shut.

Bronwyn Bancroft. Artist. Mother. Friend.

20 years ahead, frustrated in translation, awake and aware to the magic, desperate for humans to be our best — how hard is it for a human being to think?

To just stop and think, to value an idea, to value joy, to not be intimidated by forces that move bigger than them, a burst, an explosion, a crackle of light and fire, lightning is hard to bottle, it’s inside her, lightning wants to burst out and awaken the landscape, it’s her, lightning in a bottle.

Bronny B.

Underwater, swimming, swimming, swimming, water is life, return to the creek, to the water, swimming, the mind will calm, the water, the return, the return. We don’t have a choice, we are in it always, always moving, always moving, something inside, the fire, gotta be calmed, water.

Water calms. A smile.

Mother. Artist. Daughter. Friend. Ally. Trouble Maker.

Trouble Maker? The rules are stupid, don’t tell me to follow them, change them.

Thinker. Doer.

Gives away her money, her food, her rooms, everything. Always giving, others first.

Leader.

Head down, painting, painting, painting, painting, painting, painting, painting, painting, painting.

Done the work.

Now you look?

She’s not looking, she’s painting. Not for attention. Compelled, a force, the fire, the water, the life, the earth, the soul, the window in time, the only moment we get.

An artist for the ages, a burst of light and love and life, of power and passion, of joy and hope, my mum, I love her, she taught me to never ever give up on my imagination, she reminds us all of what’s possible, if we don’t stop doing.

Truth Seeker

Ella Bancroft

What an honour and privilege to be raised by this true master, this woman who never gave up, who never stopped painting, never stopped speaking her truth and never stopped reminding us that magic lives outside the confines of monetary or social status. She was always reminding us through her art that we must carry the stories of those who came before us, to remember those times and to pull great strength from our culture and ancestors.

In 2024, it’s time for truth telling, about the history of this country and about the truth of our existences and our participation in a world that uses death and destruction as a measurement for money. If you really think about the economic system, you will find that it thrives off death and destruction, the exploitation of resources, the death of old growth forests or the death of our seas. My mother has always been a Truth Seeker, a wise woman, a fierce leader, a woman who rises alongside her community, a woman who is connected to her Country. The biggest truth I will speak is that she is a woman who has given so much light and so much hope to many.

She has always painted in a way that reminded us of our magic. She reminds us of the magic of the natural world and always reminds us of where we came from and on whose shoulders we stand.

Artist

Dr Bronwyn Bancroft AM

In 2021 and 2022, I undertook the inaugural NSW Aboriginal Creative Fellowship at the State Library of NSW, funded by Create NSW. I relied on the invaluable support of the Indigenous Engagement team, particularly Damien Webb and Melissa Jackson, who sent me digital copies of historical journals, maps and photographs relating to my research, and who I corresponded with over countless emails and Zoom meetings. Much of my Fellowship was undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic and the devastating floods that engulfed the Northern Rivers community.

The Fellowship has contributed to a body of work I have been developing over a number of years. My artistic practice is inspired by my Country in the Bundjalung Nation, and my spiritual connection to my ancestors. I have dedicated my life to exploring and recording my family and their history, while also weaving in my own story as a Bundjalung woman, mother and artist.

When I commenced my first degree at the Canberra School of Art in 1977, straight from high school, I was able to rephotograph many of my family’s historic photographs, all taken by my grandfather, Arthur Bancroft, with a Brownie box camera. I have continued this work to this day, reclaiming images and incorporating them into my artistic practice. This journey is deeply personal. Creating work around my family and our resilience is paramount to my existence and my extended family as Bundjalung people.

My Uncle Pat Bancroft passed away in 2014 at the age of 94. He bequeathed to me his collection of axes, pocketknives, crystals and calcite samples. Some of these stones are thousands of years old and would have been made by family. Uncle Pat’s knowledge of Bundjalung Country was phenomenal so it was an absolute joy and privilege to learn from him.

I am in awe of my history, and the fact that my family has lived in the same spot since colonisation is to be admired.

The story of colonisation, violence and dispossession has historically only been officially documented and interpreted by the colonisers. Going into the Fellowship, I knew that the large majority of the Library’s collection was written by non-Aboriginal people. I wanted to present a more balanced perspective, using my lens as a Bundjalung woman, whose family has survived genocide and frequent attempts at dispossession.

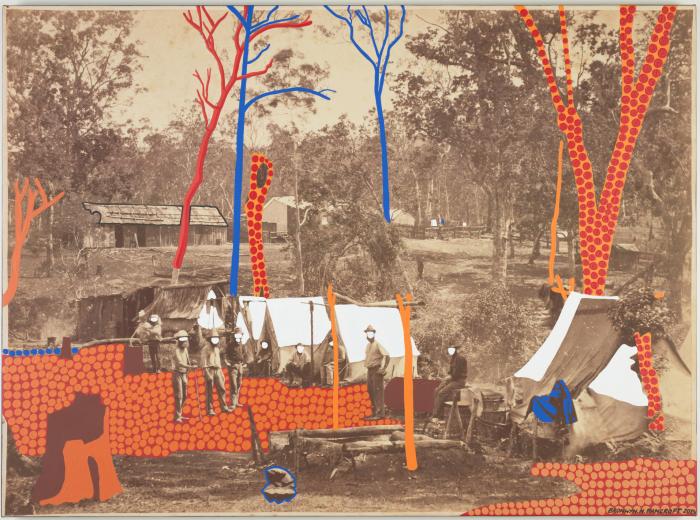

As part of my Fellowship I produced a series of mixed media artworks, which are on display as part of this exhibition and are a direct response to the historical material. These mixed media works are interspersed with my family’s collection of personal photographs and historical objects, Uncle Pat’s stone tools and axes, and my painting series ‘From the Hands of My Ancestors’.

To be able to paint on an image captured in time like this has been an incredible experience. The reclamation of these photographs brings my family history and bloodline into other people’s lives. It provides the opportunity to share a tiny glimpse of intertwined lives brought together by time and place.

The opportunity to access the Library’s collection, for which I’m grateful, has deepened my appreciation for the bravery of my mob and, also, filled my heart with immense sadness at the perils they faced. There were many tears spilled reading the journals documenting the dispersal, dispossession and murder of our people.

To be able to create an exhibition based on my family and Bundjalung Country is an honour. I believe that many conversations will ensue after visiting this exhibition. It offers a different perspective of this country’s history, and a snapshot of one family’s existence, resistance and survival.

The Curator

Cherokee Lord

Jingi Wala. It was going to be a typical, beautiful day in Byron Bay — sun shining, fresh seawater air dancing around our lungs and the evergreen countryside soothing our eyes.

It was quite easy to spot Dr Bronwyn Bancroft’s studio among the line of industrial buildings — just follow the colours! Up until then, I hadn’t had the pleasure of meeting Bronwyn but from what I had heard, she was a force to be reckoned with.

We knocked on the door and I felt a sense of ease wash over me — my body was reminded that I’m on Country and not only that, it is also my home, Bundjalung Country. We were warmly greeted by a woman oozing coolness, in a red velvet pants suit and her signature brimmed hat. Right away you notice that what you see is what you get, which made me very excited to begin working with a woman who is so sure of herself and her place in this world. There was no tiptoeing — we were marching!

As we entered her studio, we were surrounded by works she has painted over her accomplished career as an artist. I couldn’t help but try and interpret what each painting meant or intended to capture. In some way, it felt like we stepped into parts of her mind, being exposed to an intimate side of Bronwyn — this was her sacred place, her domain of creativity, and she had a comforting openness as she welcomed us into her space.

While sharing personal family stories, she would stop mid-conversation and scurry around the studio, searching for paintings, or a particular set of laundry doors from the house her grandfather had built, that she had kept and cut oval holes into to resemble vignettes, adding hand-coloured old photographs and framing them in. All while generously filling us in on her family’s rich and ever-present history.

There were many moments when my eyes were trying to absorb every bit of magnificence around me, while I was still eagerly listening to Bron’s stories of family, culture and connection to land. It was like being home and visiting one of my Aunties and having a yarn over a cuppa tea.

I pottered around, looking at the shelves of paints, surrounded by stacked canvases draped in colourful stories. I excitedly flicked through them, in awe of her ability to create such a vast amount of work, each one telling their own story and carrying a piece of her identity.

The exhibition

Damien Webb

I was delighted that the Fellowship and subsequent development of the exhibition allowed Dr Bancroft to undertake research on the ‘unsettling’ of Bundjalung Country and create a series of new works in response. Her work illustrates the forced removal of Aboriginal people from their ‘old people’s places’ by a colonialist framework that gave little thought to their connection to their homes, their Country, families, communities and clans. She pulls fragments of personal and family histories held in the Library’s collections into new and reworked forms, which draw her ancestors and family into focus.

The works explore the deep connections between Country and family, which are vital to many Aboriginal people, and run across her canvases like exposed nerves. Dr Bancroft’s newly completed works literally build upon the photographs of JW Lindt, who documented a gold mining town, Solferino, that emerged in the late 1800s on the traditional lands of the Bundjalung Nation. Her works reclaim these spaces by elevating the land, and the sentinel beings that are the trees. They restore First Nations people to Country as witnesses and reflect how it must have felt to see their places being claimed by others and are reminders of what Country was.

The artworks are presented along with a selection of belongings from Dr Bancroft’s personal and family collections — relics from Country including bush crystals, stones, knives, laundry doors and a jail hutch. The new works complete a decades-long project in which Dr Bancroft has been exploring and pulling together the threads of her family. We’re thrilled to be able to share these works with everyone.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2024.