In the trenches, in the thick of the harsh Gallipoli battlelines under the blazing Turkish sun during wartime, is not where you’d expect to find a major archaeological discovery.

Yet in 1915 at the Lone Pine landing during First World War, ANZAC soldiers digging a trench, stumbled across classical ruins from the Roman era. They found artefacts such as Roman coins and ancient pottery.

The discoveries were not just limited to pottery, they were far more phenomenal. What they’d found were the remains of two ancient Greek and Roman cities and uncovered evidence that Lone Pine – now a place of pilgrimage for many Australians – was already a place of special significance to people in the ancient world.

Associate Professor Chris Mackie, from the University of Melbourne’s Centre for Classics and Archaeology explains:

“Collectively, the soldiers’ finds identified the ancient Greek city of Alopekonnesos. This city had been known about from ancient sources, but the finds during the 1915 campaign identified with some certainty that the city was located at Suvla.”

“At Suvla Bay after the August 6 offensive the British found two Roman inscriptions written in Greek, together with various coins and other finds,” says Mackie, who has extensively researched the classical history of the Gallipoli Peninsula, Hellespont and the Dardanelles. However, this wartime discovery was just the tip of the iceberg. It turned out the whole Gallipoli peninsula was scattered with ancient artefacts and ruins.

“A British engineering unit found an important inscription dating from the second century BCE referring to another struggle for control of Gallipoli, while the French forces authorised a complete archaeological excavation of a cemetery site at Helles, uncovered when the soldiers’ picks kept striking ancient materials,” Professor Mackie says. “These finds helped to identify the important ancient city of Elaious, located at the very tip of the peninsula looking across at the Asian side.”

But Professor Mackie says perhaps of most significance to Australians is literary evidence that Lone Pine, where so many soldiers on both sides lost their lives, had been a place of special meaning for people in antiquity, and perhaps in the period since then.

“The heights above Anzac would seem to have housed ancient settlements,” he says. “We know from the diary of the Australian sapper Sergeant Lawrence that he came upon ancient pots or sarcophagi during his work digging trenches at the Pimple in 1915. Charles Bean, the official historian of Australia’s participation in World War 1, also found a coin on the path between the Nek and Russell’s Top on a visit to Gallipoli in 1919 (although he lost the coin before he could identify it).”

He says an unpublished document now reveals something more significant.

Colonel Crouch, who fought at Gallipoli during the campaign, returned to Turkey afterwards for a visit, and was invited by Colonel Hughes, an important member of the Imperial War Graves Commission, to re-visit the peninsula. In his thoughts on the visit written in 1924, Crouch pointed out that ‘it will interest the Lone Pine defenders to know that when the Commission was digging for the site of the obelisk, they discovered a Roman camp, old Roman remains, and coins, and some old skeletons’.

“So visitors to the Obelisk, while sensing the pathos and historic significance of the Lone Pine site, will now be aware that other people, from other millennia, had lived, fought and died on that very place,”

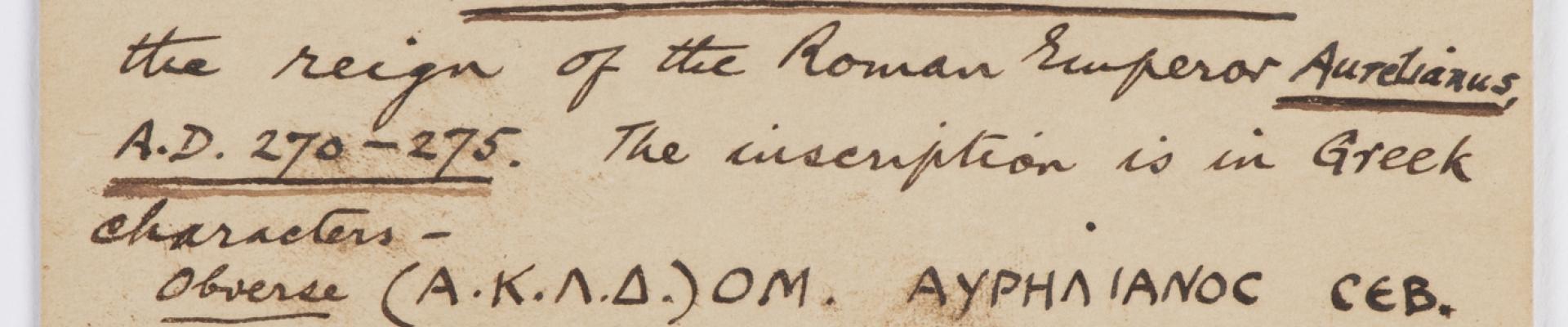

Aurelian’s coinage reform

"Aurelian’s reign records the only uprising of mint workers. The rationalis, a senior public financial official whose responsibilities included supervision of the mint at Rome, revolted against Aurelian. The revolt seems to have been caused by the fact that the mint workers, led by the rationalis, were used to stealing the silver for the coins and producing coins of inferior quality. The rationalis incited the mint workers to revolt when he was placed under trial by Aurelian. The rationalis and many of the rebels were put to death and the mint of Rome was temporarily closed.

Aurelian instituted several new mints and reformed the monetary system, including the introduction of the antoniniani containing 5% silver. These coins bore the same mark XXI (or its Greek numerals form KA), which meant that twenty of such coins would contain the same silver quantity of an old silver denarius. The Emperor then struggled to recall the old ‘bad’ coins prior to the introduction of the new ‘good’ coins.

Roman authorities at Alexandria in 274 struck a new tetradrachma on a thick, dumpy flan …"

Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700

By Kenneth W. Harl, 1996