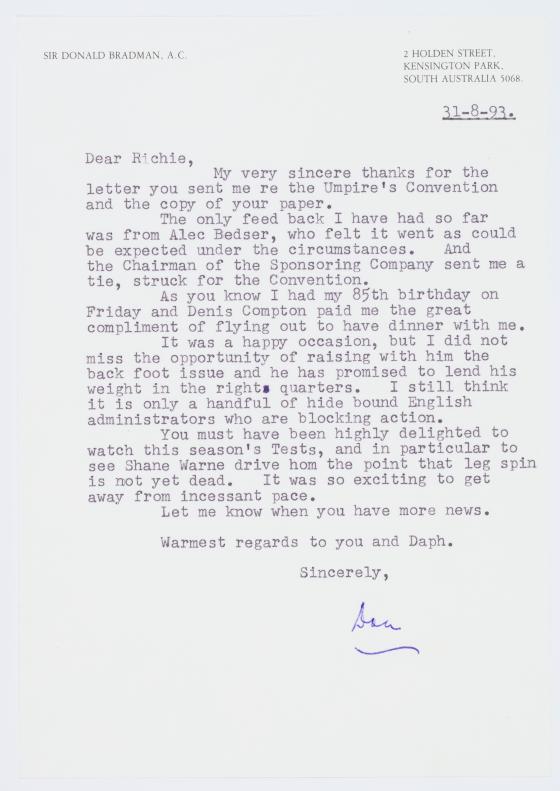

‘You are still my great white hope,’ Sir Donald Bradman told Richie Benaud, in relation to his campaign to change one of the laws of cricket. Without Benaud’s help, Sir Donald wrote, it was liable to be seen as ‘another stupid bloody Bradman exercise’.

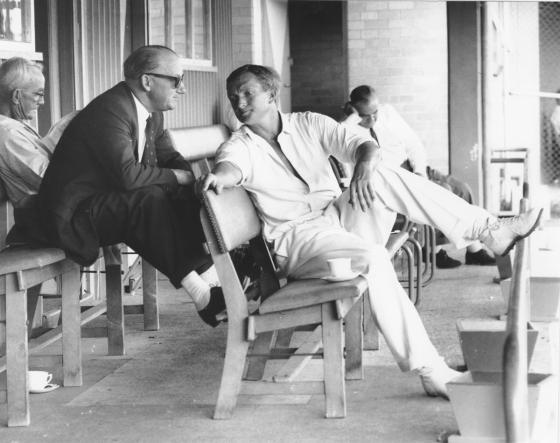

This letter was written in October 1992, when Bradman was 84 years old and Benaud 62. Considering the veneration with which both cricketers are now held, it is eye-opening to see how frustrated and ignored Bradman felt as he grew older. Letters between the two Australian greats, newly obtained by the State Library of NSW, reveal the growth of this frustration across almost two decades, from 1975 to 1993.

The no-ball rule might seem an arcane detail of cricket, but Bradman and Benaud opposed it resolutely. Down the years, it was probably the only issue upon which the three iconic Australian captains of the twentieth century — Bradman, Benaud and Ian Chappell, more often than not a staunch opponent of Bradman — all found themselves on the same side.

Benaud passed away in 2015, and his widow, Daphne, has generously donated 14 letters he exchanged with Bradman to the Library. This correspondence shows how dramatically the balance of power in Australian cricket shifted between the 1970s and 1990s.

In their first letters, Benaud was working in England as a professional broadcaster and journalist, while Bradman was operating his stockbroking firm in Adelaide and sitting as a director of the Australian Cricket Board, of which he had been chairman for two terms from 1960 to 1963 and 1969 to 1972.

In an aerogramme in May 1975, Bradman gave Benaud some advice on work–life balance: ‘Don’t you think you have reached the age when you can take life just a little bit more leisurely and just have a little bit more time to spend with your friends who enjoy your company?’ He politely declined Benaud’s request to appear at a cricket seminar he planned in Adelaide. ‘[F]rantically busy’, Bradman had decided to wind down his public appearances, apologising: ‘I’ve only done 2 functions and have turned down 2 hundred.’ Benaud persisted, replying, ‘I believe it is something you would enjoy doing’, and ‘Let us leave it with you’, before concluding with a suggestion that they have a game of golf next time Benaud visited Adelaide.

By July, Bradman was firmer, declining the golf game for health reasons and asserting, ‘Sorry I think it better for me not to do that seminar but you will get a better man.’ Benaud accepted this response in his next letter, which he filled with observations about cricket politics, broadcast-rights sales and the Australian team currently touring England.

The staples of small talk across the span of their correspondence were gossip about administrators, opinions about current players, golf chat and the future of broadcast rights which, then as now, formed the main stream of cricket’s income.

It was a dispute over those rights that caused a 14-year gap in the Benaud–Bradman correspondence. In 1976–77 in Australia, Kerry Packer’s Nine Network challenged the long-term incumbent, the ABC, for the right to televise cricket. Bradman persistently defended the governing body’s relationship with the public broadcaster and also opposed Ian Chappell’s efforts to lift the players’ pay rates. In 1977, Packer funded World Series Cricket (WSC), a breakaway tournament comprising Australia (led by Ian Chappell), the West Indies and a World XI. This divided global cricket for two years until peace was brokered in 1979 and Nine won the broadcast and marketing rights in Australia. During cricket’s ‘civil war’, Bradman, still a powerful establishment presence, was on the opposite side from Benaud, who offered advice to Packer, mentored WSC players, commentated and wrote on the WSC matches, and was the most influential senior cricketing voice on the WSC side.

It was not until 1989, a full decade after the compromise, by which time Bradman had retired from the board, that the available correspondence resumed. By then, however, the balance of influence between Benaud and Bradman had reversed. Benaud remained a commentator and ever-present guiding hand over Australian cricket, whereas Bradman felt increasingly marginalised. The flow of dinner and golf invitations went the other way: it was Bradman making the suggestions and Benaud, when in Adelaide, apologising for being too busy to eat or play golf with The Don.

On one point, however, they made common ground and felt equally thwarted. Bradman wrote to Benaud of the ‘absolute farce’ of the front-foot no-ball law slowing down play during the recent West Indies tour of Australia, what Bradman called a ‘disastrous experience’. ‘The viewing public are without doubt fed up to the back teeth with the front foot law.’

The number of no-balls registered by the fast bowlers reduced and slowed down the amount of play, and it was very difficult for umpires to properly observe the bowler’s front foot while also adjudicating on what happened when the ball arrived at the batsman’s end. No-ball calls, when made, arrived so late that the batsman had no chance to benefit from it with a free hit. Bradman had been lobbying Australian Cricket Board members without success; he urged Benaud to help him, and promised change ‘PROVIDING WE HAVE THE WILL TO TRY’.

Cricket’s laws were made by the Marylebone Cricket Club in London, which felt a long way away. If Bradman, then 80 years old, was feeling the sting of irrelevance, Benaud, at 58, was beginning to sense its onset. Calling the front-foot law ‘a wretched thing … [that] has done harm to [cricket] over the past thirty years’, he assured Bradman he was busily writing letters to newspapers, lobbying journalists, and trying to convince Clive Lloyd, the powerful recently retired West Indian captain and now manager, that his team would not have been fined $22,000 on their 1988–89 Australian tour for slow over rates if the back-foot no-ball law was in operation.

The only material headway the pair made, however, was an undertaking from the then board chairman, Col Egar, that the 1990–91 Sheffield Shield would be played under the back-foot law. Benaud anticipated England saying, ‘Why should we be interested in that change when you, in Australia, don’t even have the will to do it yourselves.’ As it turned out, Australia did not have that will. Bradman said he had heard nothing about it and feared Benaud had been ‘misled by some newspaper report’.

By late 1992, Bradman was roundly frustrated. South Africa’s cricket chief Ali Bacher had consented to try changing the law in domestic cricket there, but England continued to dismiss his representations.

His later correspondence is alternately apologetic — ‘I am not going to bombard you with correspondence’ — and also humble, thanking Benaud for reading a piece Bradman wrote for a book Tony Greig was producing on contemporary cricket. At the passing of his old sparring partner Bill ‘Tiger’ O’Reilly in 1992, Bradman was ‘sad’ but also relieved that ‘at least we have seen the end of his bigoted crusade against what he called the “pyjama” game’ plus his continuance of a feud between the two men that had persisted ever since the 1930s when they played together for Australia.

In the last of these letters, written in 1993, Bradman sounded exhausted by the fruitless campaign to change the no-ball law and was resigned to being marginalised. He commented that he had ‘my own private thoughts as to where Australia went wrong’ in the recent series loss to the West Indies, ‘but guess they should remain private. Otherwise I would get into trouble with our selectors and our captain.’ On the no-ball law, he had won the support of contemporaries in England such as Alec Bedser and Denis Compton, both also long retired, but had grown weary of ‘only a handful of hide bound English administrators who are blocking action’.

The letters offer a new insight into how even two giants of cricket such as Bradman and Benaud felt powerless to influence the course of the game as their playing careers receded into the past. Today, the front-foot no-ball rule persists, but it is governed increasingly by side-on cameras. Batters now have almost zero opportunity to benefit from having the time to hear a no-ball call before they play their shot. Bradman and Benaud would have hated that. But one new development they got to enjoy was mentioned in the last of Bradman’s letters to Benaud: he was ‘highly delighted’ to see a new young bowler. ‘Shane Warne drive[s] home the point that leg spin is not yet dead. It was so exciting to get away from incessant pace.’ Both Benaud and Bradman lived long enough to see this positive change come to full fruition.

Malcolm Knox is a journalist, author and columnist for the Sydney Morning Herald.

A selection of letters between Sir Donald Bradman and Richie Benaud are on display in our Amaze Gallery.

This story appears in Openbook winter 2022.