If you walked down a suburban Sydney street in the 1930s or 40s it’s likely you would have passed a small privately run library.

Hundreds of ‘circulating’ or subscription libraries operated from the early twentieth century to the 1960s.

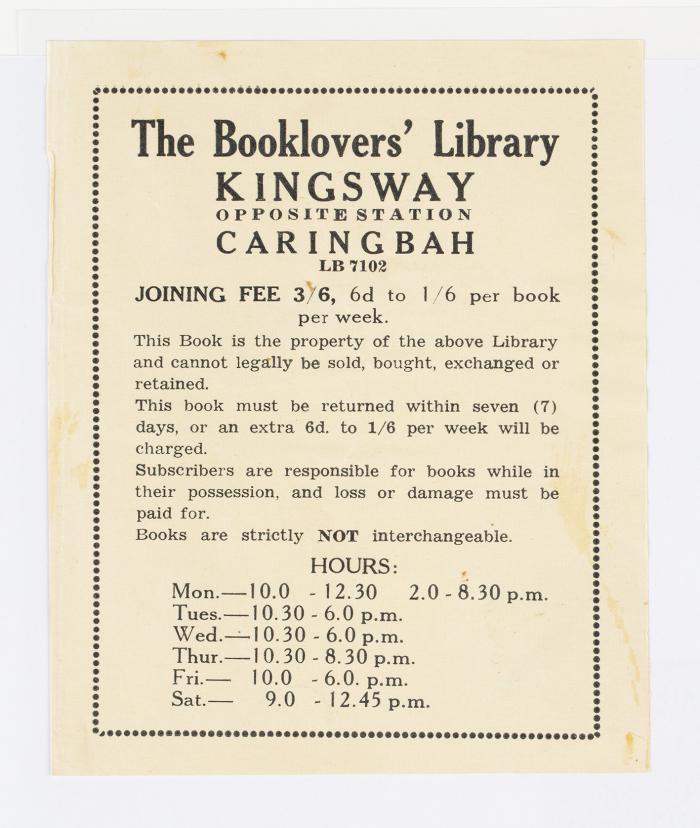

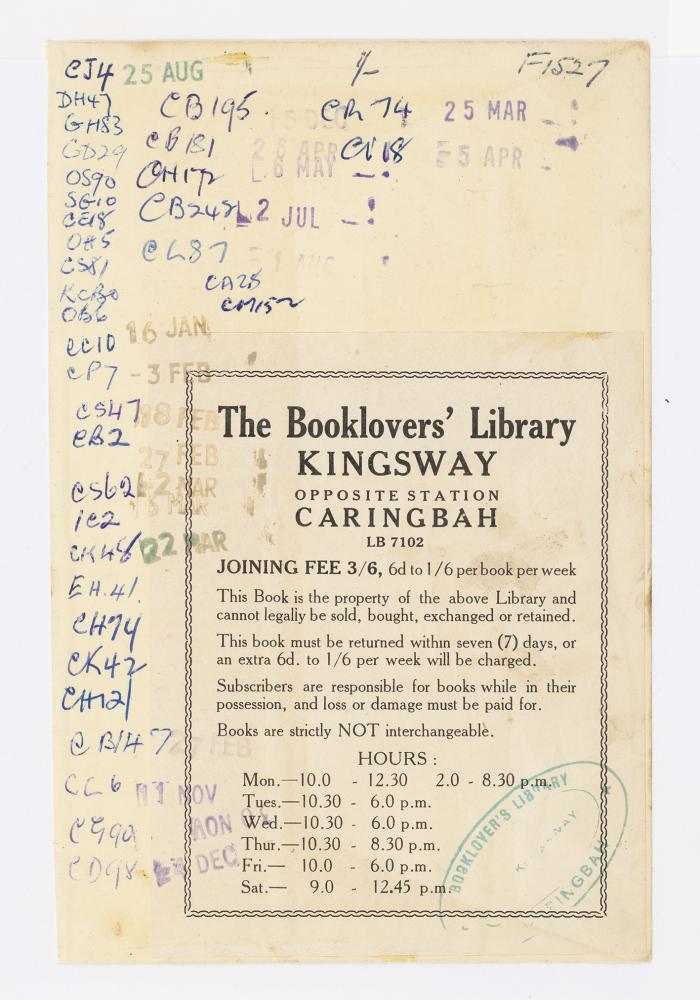

Many smaller libraries charged a one-off joining fee, while larger libraries had a recurring subscription. The Booklovers’ Library in Caringbah, for example, had a joining fee of 3 shillings 6 pence (about $14 today) and a small fee starting at 6 pence (about $2) to borrow each book. Others, like the Paragon Library at Matraville, had a simple weekly hire rate per book, with no joining fee. Either way, it was much cheaper than buying new books, especially in the Depression era between the wars.

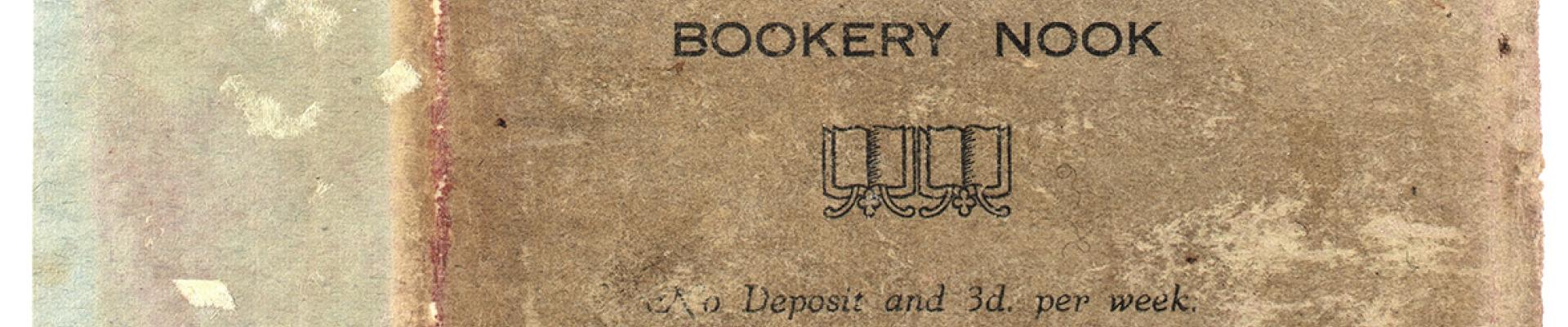

I was recently drawn into the world of circulating libraries by a request from a reader who was trying to find information about the Viking Library on Sydney Road in Balgowlah. He sent a photograph of an undated label that had been affixed to a book. It stated that the Viking’s quarterly subscription rates ranged from 6 shillings for one book at a time to 16 shillings for three books (approximately $14 to $39 today). Alternatively, you could pay an entrance fee of 2 shillings and 6 pence, and 3 pence per book (about $0.64).

I was disappointed to find no mention of a Viking Library in Trove’s digitised newspapers, so I did some wider research on circulating libraries. An early example can be seen in a photograph in the Library’s Holtermann Collection, which depicts Donald McDonald’s Circulating Library in Gulgong in the early 1870s. The number of these libraries increased steeply in the 1930s and peaked in the 1940s. By the end of the Second World War, according to book historian John Arnold, there were around 527 in Sydney.

Many of the small circulating libraries dotted through the Sydney suburbs and in regional NSW are represented in a collection of bookplates that was donated to the Library by Albert Jeffrey Bidgood. A member of the Book Collectors’ Society of Australia, Bidgood compiled this collection of more than 1500 book plates from nearly 1000 libraries of all types across Australia, dating from about 1900 to 2015.

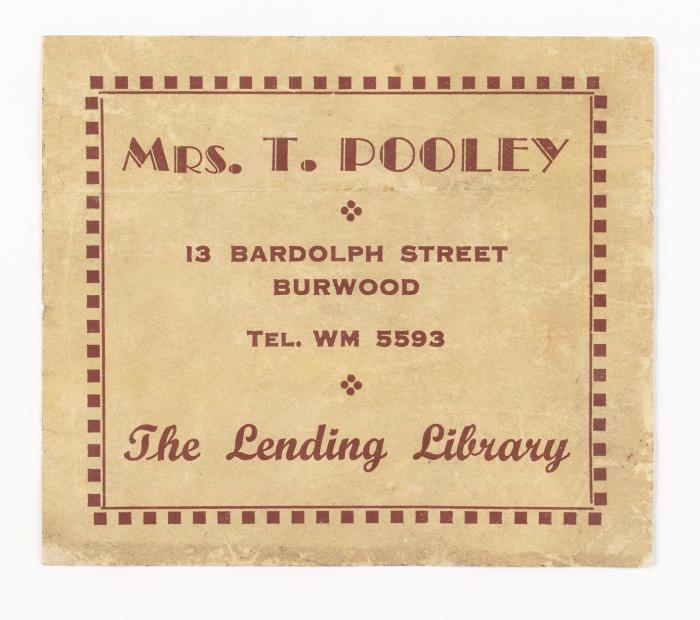

Some of the more evocative library names represented in this collection include the Seagull Library in Dee Why and the Pixie Book Inn in Coogee. Other records uncover Roseville’s Pagoda Tree Library, and Randwick’s Ding-Dong Library. But many small libraries had no other title than the proprietor’s name, such as Mrs T Pooley’s Lending Library in Burwood, or the suburb name, like Stanmore Lending Library.

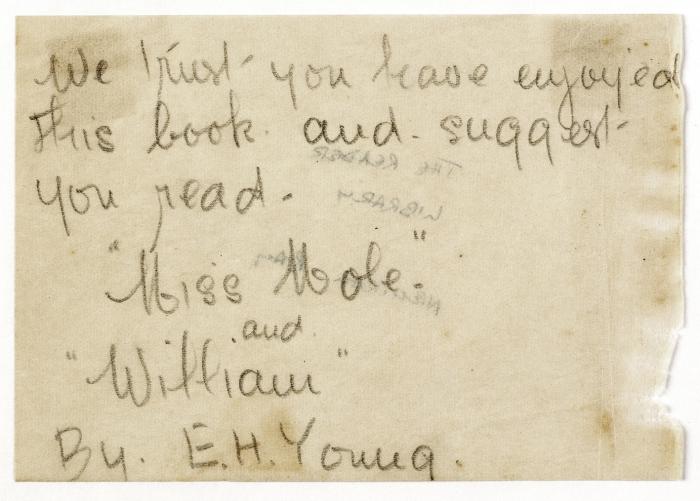

Annotations on some of the bookplates give us glimpses of individual reading lives — such as a plate from the Booklovers’ Library in Caringbah that shows handwritten borrowing records, and a note to a member on a bookplate from the Reader Library in Neutral Bay with thoughtful suggestions for further reading.

The Viking Library is not represented in the bookplate collection, and my next port of call for tracking it down was Wise’s New South Wales Post Office Directory. Published from 1886 to 1950, the directory lists businesses and services by area, and is digitised on Trove. By searching within individual directories (though not all years are searchable), you can view listings for libraries by suburb. Libraries in the Bankstown area in 1947, for example, include the Beverley, Moderne, Ideal and Mrs Edna Burton’s.

Many circulating libraries were run by married couples or women on their own, and it was clearly considered an appropriate business for a woman to manage. A 1930 advertisement for a business for sale — ‘Stationery, Library, Fancygoods. £135. In a beautiful and select suburb’ — suggests it is ‘a great chance for 2 ladies’.

I found no mention of the Viking Library in a Wise’s Directory until 1940, when it is listed at 83c Condamine Street, Balgowlah. At this time there were 14 libraries in the Manly area, six of them in Balgowlah alone!

In the following year the Viking Library is listed at 290 Sydney Road, Balgowlah, the address on the reader’s label. It appears to be short-lived, as the 1943 directory has no Viking Library, though it does have a Penguin Library nearby at 291a Sydney Road. But in 1950 the Viking Library is back again at 290 Sydney Road. Some libraries may not have paid for directory listings every year, especially when the proprietors and premises changed frequently. Among the Library’s collection of Australian library bookplates are several for the Penguin Library, one showing the street number altered by hand from 281a to 351 Sydney Rd. Some small circulating libraries moved around frequently due to changes in ownership, availability of premises and rent increases.

According to Arnold, cheap book reprints meant that a proprietor with limited means could afford a reasonable stock, but the business model of small circulating libraries still had a high failure rate. The turnover is reflected in the frequent changes in the names and number of libraries in Wise’s directories, and in the many advertisements for circulating libraries in newspapers under ‘Businesses for sale.’

These ads show the large number of mixed businesses that included libraries, such as my favourite in Concord in 1924: ‘FOR SALE, NICE LITTLE BUSINESS, BOOT REPAIRING, LEATHER, GRINDERY AND CIRCULATING LIBRARY’. This model was probably sensible, given the rates of competition and failure. Some businesses offered complementary services like stationery products and newsagency stock, and the wide range of combinations included unlikely partners such as employment agencies, florists and pharmacies.

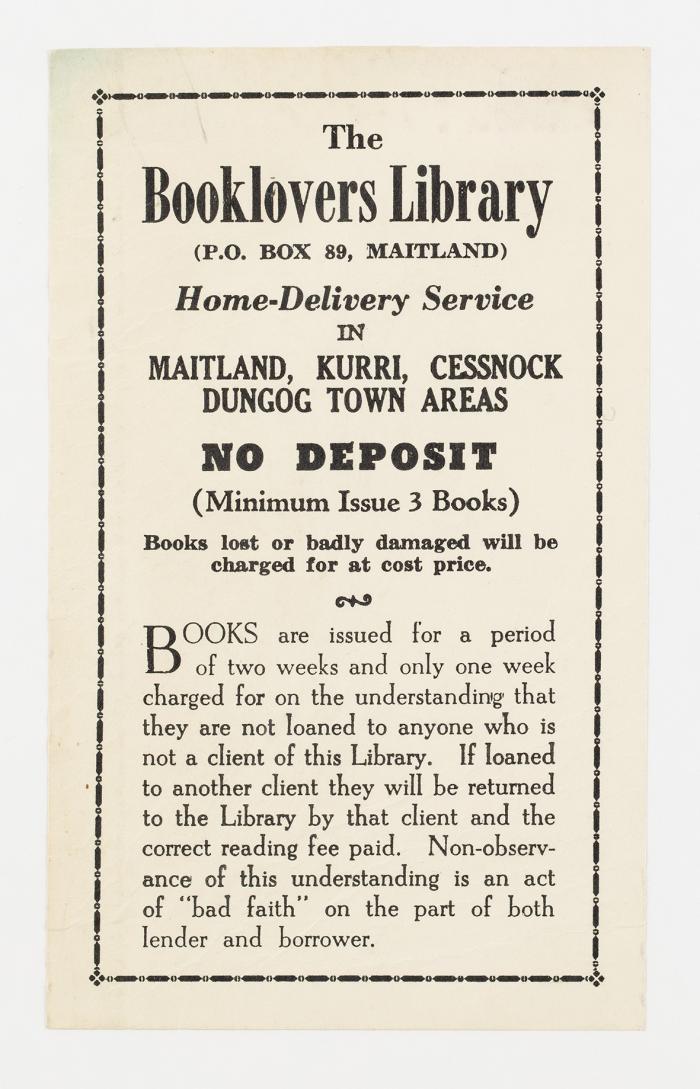

Circulating libraries promoted themselves on book labels and flyers, and larger libraries also advertised in newspapers. Some trumpeted the value of reading, while others emphasised hygiene. This was sometimes featured in the library’s name: New Vogue Hygienic Library Broadmeadow, Bartrop’s Hygienic Library Adamstown, and the Piccadilly Hygienic Library in Coogee. The Booklovers Library (‘Home Delivery Service in Maitland, Kurri, Cessnock town areas’) detailed its book care and hygiene practices on its label, under the motto ‘Clean Books for Clean People’.

A new branch of the Lomax Libraries opening in Parramatta in 1938 emphasised its devotion to hygiene in an advertisement:

One notable feature of this library is the manner in which the books are prepared. These books are covered with a preparation that enables them to be washed with a disinfectant if necessary, thus eliminating any risk of infection.

As well as providing insights into the germ phobia of library patrons, the records of circulating libraries also reveal reading tastes. A survey of loan transactions from an unnamed library in a working-class suburb of Melbourne, quoted by John Arnold in 2001, shows the following breakdown of genres:

| Romances | 25% |

|---|---|

| Westerns | 22% |

| Mystery | 21% |

| Adventure stories | 15% |

| General literature | 10% |

| Better-class novels | 7% |

The stamped front page of The Scarlet Bikini by Glynn Croudace that is preserved with a bookplate from the Bookery Nook in Neutral Bay, certainly suggests popular fiction. But it is difficult to determine membership, loan figures and readership of circulating libraries’ stock.

The NSW Library Act, passed in 1939, would eventually lead to the provision of free public library services for the people of NSW. No doubt these publicly funded libraries created competition for circulating libraries and hastened their demise. But this effect was not immediate: because of the war, the act was not fully proclaimed until 1944, and some councils took decades to adopt it. The advent of television and cheaper paperback books were other causes for circulating libraries’ decline in the 1950s and 60s, according to Arnold.

Now that these small libraries have disappeared, bookplates, newspaper advertisements and directories give us fascinating glimpses into a significant aspect of Australian library and social history. As a bookplate for the Paragon Library in Matraville puts it:

From year to year and day to day,

Whereever you may be,

A book is a friend that lightens your way

And sets you fancy free.

Jane Gibian

Librarian, Information and Access

This article is the result of an enquiry to the Library’s online ‘Ask a Librarian’ service.

Sources

John Arnold, ‘“Choose Your Author As You Would Choose A Friend”: Circulating Libraries in Melbourne, 1930–1960’, La Trobe Journal 40, Spring 1987

John Arnold, ‘The Circulating Library Phenomenon’, in Arnold, J & Lyons, M, A History of the Book in Australia 1891–1945, St Lucia, Qld: University of Queensland Press, 2001