Soupe à l’oignon

A recipe from Alma Lach’s Hows and Whys of French Cooking, subtitled A revised and expanded edition of Cooking à la Cordon Bleu published in 1974.

Ingredients

¼ pound butter

6 large yellow onions, sliced thin

2 tablespoons sugar

2 tablespoons flour

7 cups chicken stock

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon pepper

Chunk of butter

2 onions, sliced

6 (½-inch thick) slices French bread

Grated Gruyère or Parmesan cheese

Recipe

Melt butter in saucepan and then add 6 sliced onions. Cover with a lid and simmer for about 30 minutes. Add sugar and flour. Stir-cook a few minutes, then stir in stock, salt (remember Parmesan is salty), and pepper.

Simmer for 30 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasonings.

Stir-cook 2 sliced onions in chunk of butter until caramelised. Once they are browned and slightly crisp, add to the soup for colour and taste.

Toast French bread, then place in a warm oven to dry out. Fill individual earthenware bowls with soup. Put toasted bread atop the soup. Let it soak and sink into the soup, then sprinkle with cheese. Broil a few minutes to brown the cheese. Serve with plenty of crusty French bread.

Note

If lacking earthenware bowls, pour soup into a casserole, top with toasted bread slices, sprinkle with cheese, and broil (grill). If using a tureen, sprinkle the bread slices with cheese, broil, and then float atop the soup and serve.

A few words by the cook

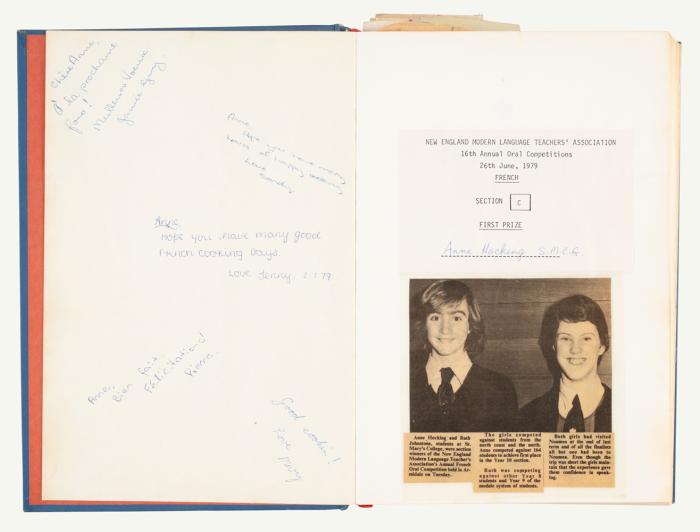

Anne Hocking is a Librarian, Collection Acquisition and Curation.

With the Summer Olympics in Paris coming up, many of us will thrill at the sound of beautiful French accents on our televisions. Some viewers might be able to exclaim a few words from our schooldays French — Bonjour Monsieur! Bonjour Madam! Bonjour mes enfants!

While the study of languages generally has taken a downturn in schools in recent years (only 10 per cent of students do a language for the HSC), for the kids in Sydney and across regional NSW in the 1960s, 1970s and into the 1980s, French language classes at school were par for the course. Loathed by some, loved by others, they gave us a hint of a wider world, a taste of an exotic culture far away from everyday life in an Australian city or country town.

I was one of those kids. Learning French in the heat of the Australian summer in Gunnedah, I dreamed of visiting Paris and watching the world go by from a Parisian cafe table or from my own Citroen 2CV. I clipped photo cuttings of La Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris and La Tour Eiffel for school projects, sang ‘Frère Jacques’ at school assembly on Bastille Day and made tons of French rum balls for special occasions. I even went on a thrilling school excursion to New Caledonia for a taste of France in the Pacific.

My proudest moment was winning my section of the New England Modern Language Teachers’ Association Annual Oral Competition in 1979. Students from all over the district travelled to the university in Armidale to test their skills with a learned French poem and a short impromptu reading piece. The winners of heats had to repeat their performance late in the afternoon in an auditorium filled with hundreds of their fellow students. My prize for this effort was a satisfyingly bulky copy of Alma Lach’s Hows and Whys of French Cooking, subtitled A revised and expanded edition of Cooking à la Cordon Bleu. It’s also held in the Library, part of a large collection that is testament to the impact that French cooking techniques and ingredients have had on Australian food.

My own father was a French teacher. He was inspired by a visit to France in his early teens, soon after World War II ended, and also by several weeks working in the vineyards and cellars of a small town in Burgundy in the late 1950s. Eventually emigrating to Australia from England, he undertook his Teaching Certificate, and his first posting was to Gunnedah High School. He completed his degree through the University of New England and went on to give several generations of country kids their first taste of French and other languages. Despite Dad’s uphill battle to persuade some students of the relevance of another language, numerous postcards from France arrived at our place over the years from his former students.

To be honest, my father used Alma Lach’s cookbook far more than I ever did. I still have it, and it still holds his paper scraps marking favourite recipes and bears the stains from years on a kitchen bench.

In preparation for a winter of French sporting commentary, and to honour my father le professeur français, I pulled the same worn copy off my bookshelf and endeavoured to cook a French classic.

Many think of French onion soup as a packet mix best used to flavour dips or another meal. However, the real thing is known to be ‘sweet, buttery, oniony and delicious’!

I found a recipe for ‘potage d’oignon’ in the 1658 edition of François La Varenne’s Le Cuisinier François, held in the Library’s rare book collection. Onion soup has been part of the French culinary repertoire since at least early medieval times. The version here first appeared in the mid-nineteenth century and is as true to French culture as the renowned frog legs and snails.

Alma Lach’s recipe is deceptively simple, although the first step should read, ‘Have a roast chicken for dinner the night before’ — just so you can make fresh chicken stock. It pays off as ‘beaucoup d’extra’ flavour.

My partner obliged with the roast chicken and ensuing stock. Then there were a lot of onions to peel and finely chop. The soup is essentially two lots of onions — the first lot cooked down until it almost disappears into the flavoursome stock, the second caramelised in a pan. We aimed for brown and slightly crisp but were careful not to burn these.

The addition of the ‘croûtes’, or toasted French bread, with melted Parmesan or Gruyère cheese is vital. Rather than broiling (aka grilling) the cheese on bread as the recipe proposes, we pressed our air-fryer into service, and in just a few minutes had pieces of gratifyingly dried bread with melting cheese on top. Floated on the soup or eaten as a side, these salty croûtes cut through the sweet creaminess of the soup.

Délicieuse indeed! Papa, le professeur français, would be very happy.