As I leaf through the pages of Ethel Turner’s fragile diaries, it strikes me that we can never really know the creators of our favourite works of fiction. We devour their works without giving a second thought to the lives they lived, their loves and losses, or the responsibilities and personal challenges they juggled, all while racing towards their publisher’s deadline.

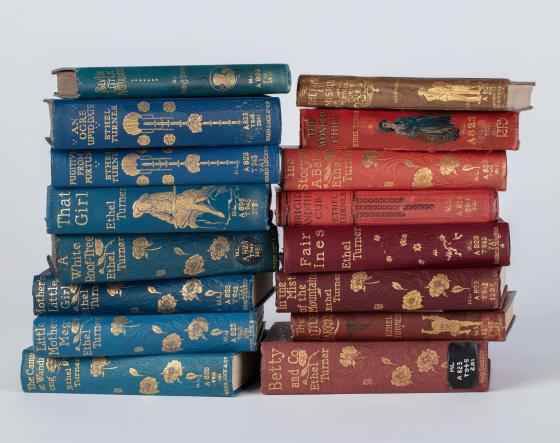

Ethel Turner’s name is synonymous with Australian literature. Her landmark first novel, Seven Little Australians, published by Ward, Lock and Bowden in 1894, was such a resounding success that she was soon referred to as the ‘Louisa Alcott of Australia’, Alcott, of course, being the author of the American classic Little Women.

In 1889, at the age of 19, Turner began keeping a diary. It became a near-daily practice for the next 62 years until 1951, seven years before her death. She recorded her daily activities, social interactions, special events and innermost thoughts and feelings with the frankness and creativity one would expect from a gifted writer. We see her future husband, Herbert Raine Curlewis, HRC, C or H, as she ultimately referred to him, slowly emerge on the page. He appears first as a contributor to the Parthenon, a magazine Turner established with her sister Lilian, and then, more frequently, as a source of frustration as he relentlessly pursued her affections. On 14 February 1891, Valentine’s Day no less, a determined Turner wrote, ‘I walked through Domain with C. and I was horrid to him, when he said he loved me, I told him I detested him with all my heart — and so I did. I don’t like him an atom.’

Her diaries reflect a reluctance to commit, which may have been influenced by her own mother’s volatile marriage to her third husband, Charles Cope. After witnessing one of their many arguments she wrote, ‘I wonder do all married people have rows. I wouldn’t be married for anything.’ She certainly took some convincing. At one stage, after some harsh words, Curlewis went so far as to return every single letter she had written to him. Turner received the parcel on 6 March 1891, along with two withered roses and a little verse book and card that she had given him at ‘Xmas’. Whether because of indecision or simply playing hard to get, the courtship plays out in the diaries over seven years. Finally, on 9 May 1891, Turner and Curlewis were engaged, but in secret, and for five years she wore the unassuming gold engagement bracelet that Curlewis gave her in lieu of an engagement ring. Turner recorded in her diary, ‘I am frightened at what I have done, and yet so happy ... I never really thought I cared for him till tonight.’ After this somewhat feisty beginning, the couple were finally married in 1896 and would go on to have a long and warm relationship.

We know all this because the Library has recently acquired the final tranche of the Ethel Turner and Herbert Curlewis papers from their family. The collection, a veritable treasure trove, includes Turner’s personal diaries from 1889 to 1951, her ‘Pen Money Book’ (where she recorded earnings from her writing), love letters sent from Curlewis to Turner during their courtship and, endearingly, a series of dance cards with names of potential suitors — including her husband-to-be, more than once across an evening — scrawled in pencil. These delicate dance cards, some with their pencils still attached, are a glorious reminder of long-gone, nineteenth-century courtship rituals.

Herbert Curlewis’s letters to Turner are full of adoration and affection in contrast, it must be said, to Turner’s more matter-of-fact diary entries. In April 1893 he ended a letter with ‘I love you I love you beyond all words my darling, darling Baby I love you I love you, Herbert’.

Turner’s diaries were not written for general viewing although her granddaughter, Philippa Poole, published a compilation of excerpts in 1979. Their new home at the Library ensures that the unexpurgated diaries are available for public access for the first time, allowing researchers to read and engage with an intimate record of a life full of ambition and aspiration. The diaries document the challenging roles Turner juggled throughout her lifetime — lover, housewife, mother, grandmother, citizen and writer.

A diary entry from 10 January 1902 captures this balancing act:

there are too many ‘departments’ in life to be head of — probably as it is I am a bad manager. But there is the roll-top desk department, & the garden (a big matter at present) & the nursery, which mustn’t be neglected, & Society — which is neglected — I’ve a 100 calls at least owing I believe — & the Clothes department & the House Linen & the Pantries, & the orders & the servants … And then there is shopping. And the calls of one’s family, — & the rights of one’s husband to have me at leisure in an evening, & letters & accounts &&&&

Turner was an independent, career-driven, successful writer by the time she married Herbert Curlewis. She sought independence early in her career and writing was a respectable way to make an income. She quickly earned the respect of men in the literary fraternity, who soon realised she could be relied upon to deliver quality pieces for their publications. In November 1892 she took charge of ‘The Children’s Corner’ in the Illustrated Sydney News, under the pseudonym Dame Durden. For almost 40 years throughout her career, she edited several children’s pages and supplements across four different newspapers.

Turner took her roles and responsibilities as a married woman very seriously, yet still managed to sustain her writing. In addition to her editorial roles, she wrote for newspapers and magazines including The Bulletin, Illustrated Sydney News, Town and Country Journal, the Daily Telegraph and the Sydney Morning Herald, always careful to record every penny she earned. In 1894, the year Seven Little Australians was published, Turner recorded an income of £159, which grew to £377 the following year. She wrote steadily through the war years and, with her growing success as a writer and editor, by 1923 her earnings of £1543 exceeded her husband’s judicial salary of £1500.

The diaries reveal her personal drive and determination as well. In December 1889 she wrote, ‘I’ll be a Millionairess soon.’ In 1893, a week before sitting down to write the novel for which she would become famous, she wrote in her diary, ‘I do want fame — and plenty of it!’

Yet, although she was gifted creatively, Turner was no free-spirited bohemian. She had a public persona, and perhaps being the wife of a judge dictated the social circles in which they moved. She regularly attended official functions and was comfortable in society.

Simultaneously, she threw herself wholeheartedly into domestic life and was determined to succeed as a homemaker and mother. In the early days of their marriage, the Curlewises, a tight-knit unit working to build a home together, were careful with their money and despite the flow of royalties from her books, they made the curtains and furniture for their Mosman home themselves.

Turner approached motherhood with confidence and passion. Her daughter, Jean, arrived in February 1898, followed by a son, Adrian, in January 1901. Despite the new additions to the family and requisite changes to routine, Turner didn’t miss a beat, managing to deliver a book each year with The Camp at Wandinong in 1898 and The Wonder-Child: An Australian story in 1901, the year of Federation. Diary entries from these years are full of childhood achievements and happy accounts of regular family holidays to the Blue Mountains and Palm Beach. Jean, the apple of her mother’s eye, had a gift for writing and produced four novels herself and articles for various magazines before her death from tuberculosis in 1930, at the age of 32. This tragedy greatly affected Turner who, in the remaining 28 years of her life, never completed another novel. Her son, Adrian, became a judge like his father and was very active in public life.

His own children, Ian and Philippa, were a source of great joy for Turner and helped fill the void left by Jean’s absence. Turner’s output was prodigious; in addition to her freelance writing, between 1894 and 1928 she averaged one novel per year, producing 44 books in her lifetime. She documented the moment she began working on each of these titles. The year 1893 was particularly momentous for Turner and it is exciting to watch Seven Little Australians unfold on the page, especially in her own handwriting. On 24 January, which happened to be her birthday, she scrawled in the margins: ‘Seven L. Aust — Sketched it out’, and made the life-changing decision to save the work for a book publisher, rather than a newspaper: ‘I don’t think I’ll let it go to the Illustrated, if I can do without it there, I’ll see if I can get it published in book form.’ Later that year, on 18 October she records: ‘Morning wrote chapter XX 7 Australians, killed Judy to slow music.’ On 2 November she wrote, ‘Walked up to post and sent 7 L. Australians to Ward Lock Melbourne. It took 18 stamps.’ The reply came just one week later — they wished to negotiate for immediate publication.

She found time for writing as the opportunity arose, often working late into the night when inspiration struck. On occasion, Curlewis’s mother would mind the children, which allowed bursts of creativity and up to ten hours of solid writing time. At other times Turner sought refuge in the Blue Mountains, which offered peace and solitude in which to write her latest novel.

Her growing interest in social issues meant that when she wasn’t writing, keeping house or performing motherly duties, Turner devoted time to a swathe of charitable causes. Jumping into action during times of national crisis, she formed committees, attended rallies and wrote newspaper and magazine articles to raise awareness for the latest cause. In November 1902, she penned an ‘Appeal for Bush Sufferers’ in the Daily Telegraph in support of those experiencing extreme hardship during the drought. In March the following year, she spent 11 hours fundraising on ‘Drought Saturday’ at Mosman Wharf.

Ethel Turner’s diaries give us a candid account of her rich and busy life from when she was 19 through to her 81st year. During her lifetime it was unusual for a woman to continue working after marriage so Turner’s ability to balance her public persona with her roles as mother, housewife and citizen, while finding time to produce writing from which she made a sizable income, is nothing short of amazing. Her achievement as perhaps Australia’s greatest writer for children, and author of an Australian classic that has never been out of print is one thing; the incredible life she lived is altogether another.